An analysis of a nationwide measure of 23,000 students' perceptions of growth mindset shows meaningful differences in what students believe they can change and a gender gap.

Last school year, David Andrews, a social studies teacher at Piedmont Hills High School (Calif.), noticed something in his students that puzzled him.

As a teacher of six years, Andrews had read the research by Stanford Professor Carol Dweck and others that showed the impact of having a growth mindset on students’ learning and academic achievement. Andrews promoted this belief that people can work deliberately to change their most basic abilities — namely their intelligence.

“Students are so varied when it comes to their mindsets,” Andrews said. “I’m still working to crack the enigma of how to support all my students’ beliefs about themselves.” He would overhear students saying they were good at social studies, but would never be good at math. Other students would say they could always work harder to do better in class, while some felt they just weren’t that talented.\

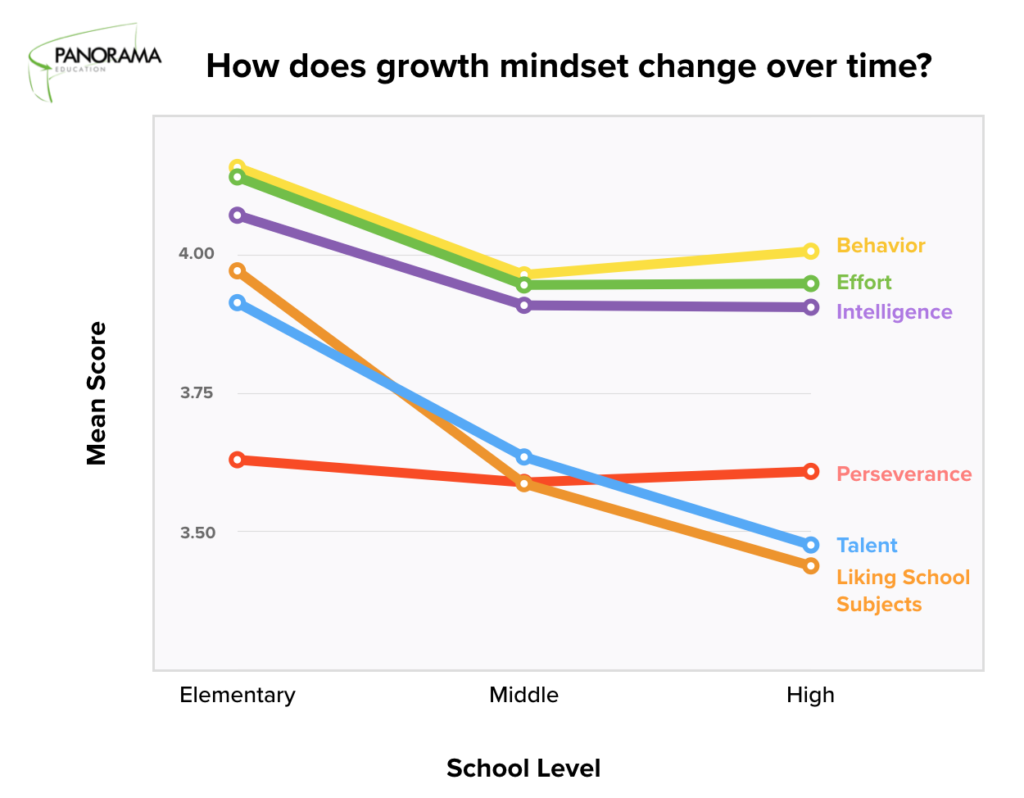

While the popular definition of mindset is based exclusively on intelligence and provides the binary labels of “fixed” or “growth” mindsets, Andrews saw something different. His students appeared to reflect growth mindset across an array of dimensions and each in their own way.

Andrews noticed that each of his students reflected a spectrum of growth mindset.

What do the data say about growth mindset?

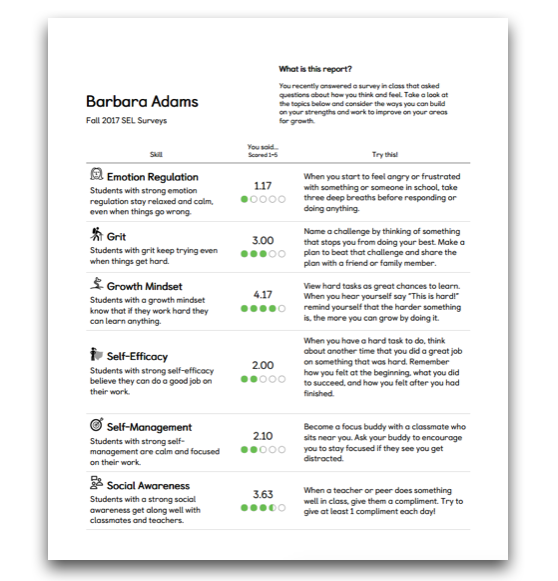

After listening to stories from educators like David Andrews about what growth mindset looks like in their classrooms, we at Panorama Education wanted to understand how students view their own growth mindset. So we looked into the data from our measures of social-emotional learning, which include responses from over 23,000 middle and high school students on the following growth mindset question:

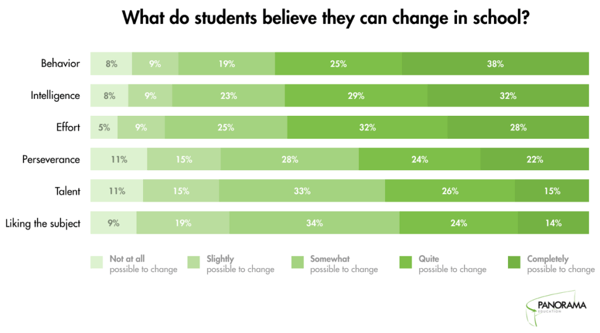

Whether a person does well or poorly in school may depend on a lot of different things. You may feel that some of these things are easier for you to change than others. In school, how possible is it for you to change:

- Being talented

- Liking the subject

- Your level of intelligence

- Putting forth a lot of effort

- Behaving well in class

- How easily you give up

This question allows students to rate how possible it is to change many different aspects that facilitate success in school — not just intelligence. Based on the results, we’ve found that students’ beliefs vary across these aspects, illuminating a more multifaceted perspective on growth mindset.

While teachers like Mr. Andrews encourage students to believe they can grow their intelligence, 61% of students felt this is “Completely possible” or “Quite possible.” Yet only 38% said the same about liking the subject in school despite the fact that teachers can play a big role in promoting students’ academic interests.

While teachers like Mr. Andrews encourage students to believe they can grow their intelligence, 61% of students felt this is “Completely possible” or “Quite possible.” Yet only 38% said the same about liking the subject in school despite the fact that teachers can play a big role in promoting students’ academic interests.

As many educators search for ways to “teach” social-emotional learning skills, these results may come as a surprise. Whitney Harris, a Dean at Uplift Peak Preparatory School in Dallas, Texas, was surprised when she received her school’s results from our social-emotional learning measures: “I was surprised to see students’ growth mindset about talent was so low. I think we’ve done a good job instilling in our students that they can behave well in class or work hard,” says Harris. “But we haven’t put that same emphasis on helping students’ develop these beliefs in other areas.”

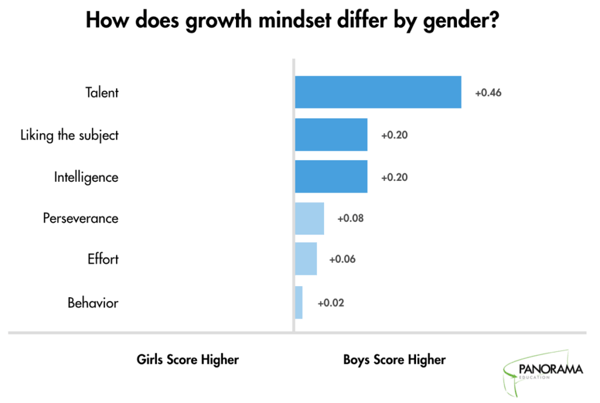

So if students reflect growth mindset differently across these many dimensions, then how do different groups of students show growth mindset? We first examined whether boys and girls reflect growth mindset differently.

We found that boys and girls show meaningful differences on our growth mindset measure. Overall, boys report a higher growth mindset score than girls that is statistically significant in three of the six aspects we measured (represented by darker shading in the figure above). The widest gap between genders is in talent, where boys record an average score 0.46 points out of 10 higher than girls. Almost half (46%) of boys reported that it is “Quite possible” or “Completely possible” to change their talent, while a little more than a third (35%) of girls said the same.

These results make us consider the implications for how different students reflect varying degrees of growth mindset. How might socialization and cultural factors discourage girls from believing their talent can be changed in the same way boys do? By digging into the data, we may gain new insights into some of the persistent challenges we face in education, such as promoting girls’ interest and confidence in STEM subjects, which may help us target smarter SEL interventions.

For Whitney Harris, these types of findings at her school add a quantitative lens to her interactions with students: “For some it’s just numbers. But to me the data align pretty well with what I’m seeing every day in our students.”

What can we learn from the growth mindset data?

There are still many questions about fostering growth mindset in our students. But the data highlight the ways in which we can grow our own understanding of growth mindset as a multifaceted construct.

How do we support students in developing multiple dimensions of growth mindset? How can we support girls to believe they can grow their talent? By collecting and analyzing data about students’ social-emotional learning, we can begin to answer these questions and more.

As students head back to school this month at Uplift Peak Prep, Whitney Harris will be looking for improvements in the next round of data: “It’s at the forefront of everything we’re doing. We have such a huge influence on our students in our capacities as teachers and staff members. It starts by changing our mindsets as adults.”

David Andrews will return to Piedmont Hills High with a renewed focus on supporting his students’ varied mindsets: “That is a challenge of education and one of the joys of teaching,” he says, “being able to help students believe in themselves in all aspects of their lives.”

This post originally appeared on Education Week’s “Finding Common Ground” blog.

.png?width=350&height=212&name=pano-ft-rsrce%20(1).png)