For middle and high school students, teacher-student relationships lie at the center of their educational experience. If you think back to your own educational experiences, this idea is rather intuitive; it’s unlikely that you can recall specific questions from a test or even your final grade in a class, but you may always remember the personal connections you made with a favorite teacher.

We know from Panorama's student surveys how students view their relationships with teachers. Such positive relationships can lead to better educational outcomes for adolescent students. But how can we improve teacher-student relationships in the classroom?

Background

Dozens of social psychological studies find that when people believe they share commonalities with others, their relationships improve. If you favor a certain sports team, musical genre or set of beliefs, it’s likely that you will have more positive relationships with others that share these same preferences.

With a research team at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, we set off to better understand how “social connectedness” could be applied to a secondary school environment. If knowing shared interests or similarities could improve relationships between two people, could we similarly improve teacher-student relationships in a middle or high school?

Of course, teens are not predisposed to cultivating strong social connections with their teachers; the various interests and values shared amongst teenagers are often not shared between teachers and students. No intervention can make teachers suddenly prefer listening to Justin Bieber over Fleetwood Mac.

Still, students and teachers often have more in common than they might think. Perhaps the student and the teacher both believe that mutual respect is more important than sense of humor in teacher-student relationships, or perhaps both want to go to the World Cup someday. We set out to explore whether helping students and teachers identify things they had in common could improve relationships --and student outcomes.

Download the Panorama Student Survey to measure teacher-student-relationships

The Study

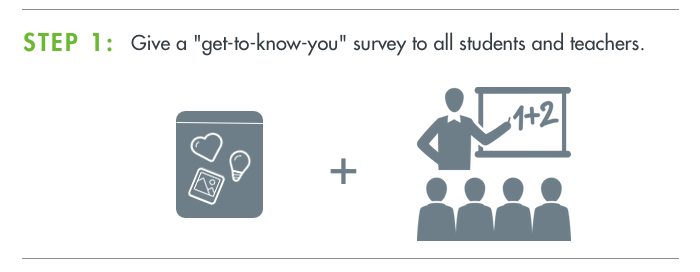

At the beginning of the school year, we gave 315 ninth grade students and 25 of their teachers a getting to know you survey during their first period classes. In the survey, teachers and students responded to the same questions that asked about personal preferences such as favorite hobbies, charities they would support, and characteristics of a good friend, among others.

Other survey items were more focused around the classroom: “I think students learn most when: (a) The teacher leads class discussions, (b) Students work independently, or (c) students work in small groups.”

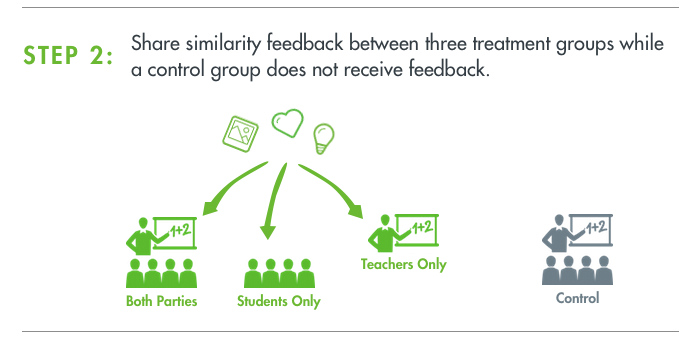

A week after the initial survey, we assigned teachers and students into four groups:

Group #1 - In our control group, neither students nor teachers received feedback on similarities.

Group #2 - Students received a list of 5 things they had in common with their teacher; teachers received no feedback on commonalities with these students.

Group #3 - Students received no feedback on what they had in common with their teacher; teachers received a list of 5 things they had in common with these students.

Group #4 - Both students and teachers received a list of 5 things they had in common with one another.

The Results

Five weeks after our “get-to-know-you” survey, all groups filled out a more comprehensive survey to gauge the impact of knowing these similarities. For additional analysis, we also gathered classroom grades at the end of the quarter. Here’s what we found:

- Teachers and students who learned what they had in common with the other party perceived themselves as being more similar.

- When teachers learned that they shared commonalities with their students, they rated their relationships as more positive. (By contrast, the intervention did not significantly affect students’ perceptions of their relationship with their teachers).

- Finally, when teachers received similarity reports about what they had in common with a randomly selected group of students, those randomly selected students earned higher grades in the class.

Additional analyses led to an interesting, albeit, more speculative finding. Many brief interventions such as this one have a history of being disproportionately effective for certain students. We examined the students who are often well-served in schools (White and Asian students) separately from those who have been historically underserved (primarily Black and Latino students) by schools in this country. These analyses suggest that the intervention was most effective in helping teachers connect with the historically underserved students. On average, the achievement gap between the well-served and underserved students at this school is reduced by over 60%, as measured by course grades. Click here to read the full working paper for more detailed analysis and figures.

Conclusion

Although it’s premature to make broad recommendations from a single study, we do think that this study underscores how important teacher-student relationship can be. The study provides an important illustration of how similarities might be leveraged to improve these relationships in secondary schools. We’re excited to continue similar studies going forward with the goal of helping teachers find effective ways to bolster social connections with their students.

Dr. Hunter Gehlbach is the Director of Research at Panorama Education and holds the position of associate professor at the Gervitz School of Education at UC-Santa Barbara. Previously, he taught social studies at a high school in Pennsylvania. Follow @HunterGehlbach on Twitter.

.png?width=350&height=212&name=pano-ft-rsrce%20(1).png)