I promised myself I would never use a stock image in an article, but I broke that rule here for two reasons.

First, it captures essential elements of psychological well-being. The students are smiling and socializing, and show us the importance of emotions and close relationships.

But I also chose this image because outward appearances aren't everything. We cannot know how these students feel or understand their relationships with each other without asking them.

In fact, these students are not close friends enjoying school. They're child actors and strangers in a stock image photoshoot.

If we want to truly understand and address students’ well-being in schools—especially this year, as students re-enter the classroom after extended exposure to uncertainty and trauma because of the pandemic—observing their behavior isn't enough. Assumptions and inferences about their well-being aren't enough.

We need to ask students to share their inner experiences. We need to center our approach to well-being in student experience and student voice. We need to build systems to thoughtfully measure and support well-being based on whole-child data.

So, what is student well-being and how can you measure it?

Student Well-Being: What It Is and Why It's Important

Well-being used to be thought of as the absence of risky behavior or mental illness. In the past two decades, however, the field of positive psychology has helped redefine well-being as the positive experiences, thoughts, and feelings that enable students to thrive.

Students’ social-emotional well-being matters and is connected to their achievement in school. There are two key components of well-being that we'll define and discuss: emotions and social support.

The positive and challenging emotions that students feel are key characteristics of their psychology, indicators of their well-being, and mediators of their success in school and life.

Supportive relationships with peers, school staff, and family members both indicate and promote student well-being.

1. Emotions

Let's start with emotions, which are central to well-being.

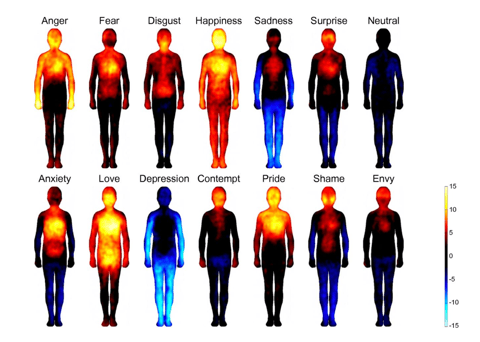

Source: Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Hari, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2014). Bodily maps of emotions

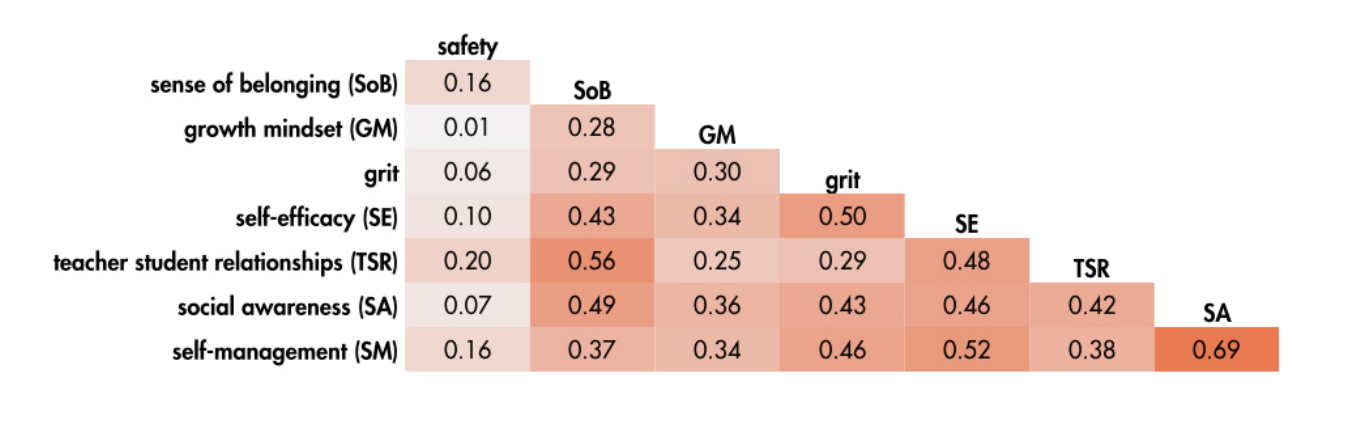

Emotions are distinct psychological experiences with accompanying physiological signatures. In the image above, people defined 14 different emotions in terms of their bodily experiences. Red areas represent increased activity, and blue areas represent decreased activity. This shows that emotions are not monolithic. In measuring and understanding well-being, we have to account for different emotions, not just one.

It's also important to consider both pleasant and unpleasant emotions. Just like mental health is not the absence of mental illness, pleasant emotions (like happiness) are not merely the absence of unpleasant emotions (like sadness). In education, for example, researchers found they can better predict students’ academic engagement from looking at measures of both pleasant and unpleasant emotions, rather than looking at only pleasant or only unpleasant emotions.

So we know we have to look at different emotions, including both pleasant and unpleasant emotions. Next we need to figure out what to query about these emotions when measuring well-being: Should we ask students how frequently they feel each emotion or how intensely they feel each emotion?

It turns out that the best thing to measure is emotional frequency. How often individuals experience emotions is a better predictor of overall well-being than emotional intensity (and other aspects of emotional experience, like stability or clarity). Frequency is also a better predictor of social and academic outcomes.

But emotions aren’t everything. Or, even if they are, they don’t exist in a vacuum. Like almost everything that matters for kids and adolescents, they exist within an important social context.

2. Supportive Relationships

Supportive relationships are another central player in the story of our individual and collective well-being—and in the everyday experiences of young people. Here is what the literature suggests about social support.

- Support saves lives. People who feel supported by close social relationships live longer than those who are socially isolated. Social support protects us from the ravages of stress, helps us avoid or escape from depression, and benefits us in varied ways that researchers are only beginning to fully understand.

- Support can be emotional, informational, or tangible. Like emotions, support is not monolithic and comes in various forms. For example, we can help students with a hug, advice, or a letter of recommendation. The positive impacts of social support depend, in part, on matching the type of support given to the type of support needed.

- Support is perceived, not just received. Support is a subjective experience. The perception of support matters just as much—and sometimes more—than any actual support received. Even when you don’t actually receive any support, knowing that you would receive support if needed is itself a form of support.

- Students receive social support from three key sources: family members, peers, and teachers. In one large study using a nationally representative sample, for example, students who felt supported by their families, peers, and their teachers had fewer school absences, spent more time studying, were more engaged in school, and got better grades than other students. Research also shows that social support from teachers and other school adults is particularly important, especially for students from marginalized communities.

These and related findings show the importance of understanding supportive relationships when building systems to support well-being, and building systems to help kids feel supported by both peers and adults.

Measuring What Matters: Student Well-Being

We've covered the foundations of well-being and why emotions and social support are integral to understanding student well-being.

Now, let's talk more specifically about how to measure student well-being.

Although there are important objective components to student well-being—such as sleep, physical activity/physical health, and stable housing—we recommend focusing on students’ subjective experiences when measuring well-being.

How are students interpreting their reality and experiencing their lives? Are their days mostly filled with moments of loneliness and anxiety, or with happiness and excitement? Do they feel safe and supported by trusted friends, family, and adults at school? Like in that stock image from the introduction, we need to understand how students experience their lives, not how adults perceive their behavior.

Students’ experiences matter as ends unto themselves; are important mediators of health, social, and economic outcomes; and, ultimately, are valued by educators, students, and families.

Students’ experiences matter as ends unto themselves; are important mediators of health, social, and economic outcomes; and, ultimately, are valued by educators, students, and families.

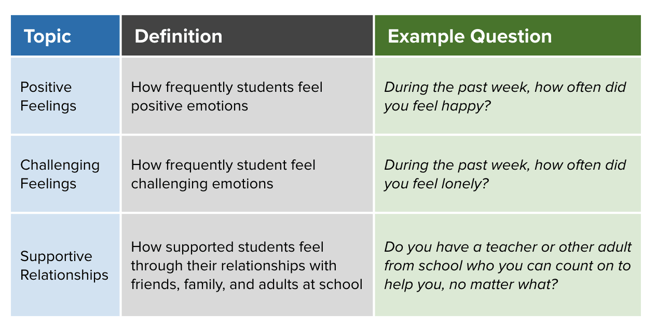

Based on the scholarship above and more, we developed the Panorama Well-Being Survey for elementary, middle, and high school students. The instrument is composed of three topics: Positive Feelings, Challenging Feelings, and Supportive Relationships.

Our goal was to create a reliable, valid, and practical instrument that educators can use at scale in schools to measure and support students’ well-being, not to design a clinical instrument for diagnosing mental illness or predicting suicide.

To create the instrument, we followed best practices in the science of survey design, tested it with 100 secondary schools, and collected feedback from school district leaders and educators to increase its psychometric qualities and practical utility. We also had a few special considerations:

- Keeping the survey short so it could be administered frequently or alongside other survey content, such as our social-emotional learning (SEL) scales

- Because of the pandemic, designing the survey questions to accommodate remote, hybrid, and in-person learning environments

- Asking students to reflect on their emotional experiences over the past week (opposed to the past day or month), to be sensitive to change while also capturing more than fleeting moods

- Choosing the topic name “Challenging Feelings” over “Negative Feelings” to encourage accurate and equitable interpretations of student data. Students experiencing high levels of loneliness may be responding appropriately to challenging life circumstances. For example, students experiencing high levels of anger may be responding productively to systemic racial injustice. We should not label those students as “angry,” their reactions as negative, or assume that they, as opposed to their circumstances, are responsible.

We typically recommend that school districts administer the Well-Being Survey twice yearly (to determine universal Tier 1 supports) and follow-up with more frequent well-being check-ins throughout the year (to determine targeted supports).

Download the Panorama Well-Being Survey

Understanding How to Use and Interpret Well-Being Data

Just as student well-being deserves thoughtful measurement, it also deserves thoughtful interpretation by educators. Panorama's survey content and platform enables the former, but educators’ knowledge and wisdom determines the latter.

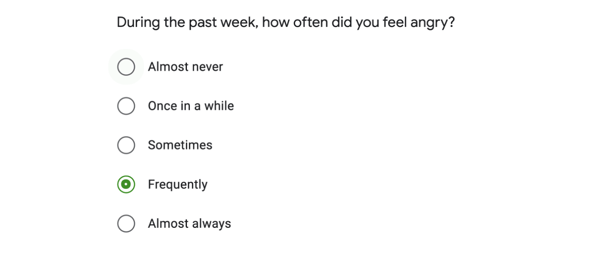

Let's look at a sample student response to the Well-Being survey:

This student is telling us that they frequently felt angry during the past week. But we can't possibly interpret this response without context. Accurately interpreting student well-being data requires contextual knowledge about students and their environments—the personal, situational, and systemic factors that shape well-being.

In other words: Well-being data should prompt educators to consider whether or not students are being supported by Tier 1 systems. Well-being isn't something to be fixed, but as adults, we can create conditions that enable students to thrive.

It’s also important to appreciate that everyone’s journey through school involves social-emotional ups and downs. An emotion that is considered negative in one culture or context can be considered positive in another, happiness can have a dark side, and emotions like anger or sadness can have upsides. Diversity in our emotional ecosystems is a good thing.

Lastly, challenging moments of loneliness, frustration, or anxiety that serve as adaptive signals or growth opportunities are categorically different from chronic or extreme periods of suffering that interfere with daily functioning.

Additional Resources

- Read: How Oregon's Salem-Keizer Public Schools is measuring student well-being with Panorama (via Keizertimes)

- Watch: How Aldine ISD (TX), Pittsfield Public Schools (MA), and Ogden School District (UT) measure and support student well-being (via Education Week and Panorama)

- Download: Panorama Well-Being Survey instrument

Dr. Sam Moulton, Ph.D., is the Director of Research at Panorama Education. His background is in psychological science, and his passion is applying social science to education. In his work at Panorama, he applies his expertise in educational psychology, research methodology, and statistics to projects that include survey scale development, social-emotional learning, multivariate and multilevel modeling, statistical inference, and data visualization. Dr. Moulton holds B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees in psychology from Harvard University and worked previously as the Director of Educational Research and Assessment for the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching.